Cool vines will live a warmer life

Champagne is a wine from a cool climate. A basic condition for more than 300 years.

Currently a vine in Champagne will produce grapes for more than 30 years. This means that when we plant a Chardonnay-vine or a Pinot Meunier these days, it will be active until at least 2050 or longer. By then an already warmer climate will have changed even more.

The grapes are already different these days. In fact, they are mostly better than they used to. This is a big advantage in a small company like ours. We do not depend as much on blends of reserve wines, plots, or different types of grapes to make good champagne. This is something we have taken advantage of since 2013, when we began making a new type of single plot- and vintage champagne: we call them our singles.

But what can we expect from the years to come? Which champagnes will we be able to make in 10, 20 and 30 years, and will they taste the same as today? Will it be sufficient for us to change our working methods, or should we expect to plant new varieties that thrive in a warmer climate?

The three grape varieties

Nowadays, the trinity of grapes in Champagne is called Chardonnay, Pinot Meunier and Pinot Noir. They are the basis of the current champagne wines.

Chardonnay (picture 3) is one of the most widely spread varieties in the world. It thrives whether the climate is cool or warmer. Originally, the Chardonnay came from Burgundy, travelled north to Champagne where the wines made from it express themselves in mineral and lively ways.

Pinot Noir (picture 1) has been cultivated in Champagne for a long time. Maybe, it came from the south with the Romans once upon a time? Or at least from Burgundy? It prefers a cool climate like in Champagne or Burgundy, where it expresses itself in wines of great finesse.

Finally, the Pinot Meunier (picture 2) is known mainly in the Champagne-region, where it is widespread in the Marne valley. It is one of several mutations of the Pinot Noir, and it has been grown in the region even before the sparkling champagne was invented. The grapes of Pinot Meunier make wines, that are round and fruity and with an unfair reputation – we believe – from old days of being less noble.

“Nowadays, 100 years later, we still pretty much work the same way.”

Original grape varieties

With time, this trio replaced close to all the original grape varieties in Champagne. Fromenteau disappeared and is no longer allowed in the production of champagne. Arbane, Petit Meslier, Pinot Blanc and Pinot Gris are still grown but in extremely limited numbers of 0,3% of the total 34.300 hectares. Nowadays they are quite in demand to produce niche champagnes.

Our plots are planted with Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier, approximately 60% Chardonnays and the rest is mainly Pinot Meunier and some Pinot Noir. In the region as a whole you will find 30% Chardonnays, 38% Pinot Noirs and 32% Pinot Meunier (Rounded numbers).

These grape varieties were chosen in the early part of the 20th century because they demonstrated an interesting balance between sugars and acidity, a complex palette of flavours and good qualities regarding the prise de mousse, which is the natural process, where the wine becomes sparkling.

Management according to AOP-rules

The vines grow along a trellis. This method began in Champagne in the early 20th Century. At that time, winegrowers and champagne houses faced the enormous task to replant the vineyards entirely. These had become wiped out by the Phylloxera-pest, an insect that destroyed the roots.

This work got to a temporary stop by World War I. After the war, the committee of replanting Champagne’s vineyards took the opportunity to introduce the trellis and a high density. A look that since then characterizes the lines of vines in Champagne. This system was found to fit the growth and to be superior to manage better in the cool climate than previous ones.

Nowadays, 100 years later, we still pretty much work the same way.

Stating the geographical area

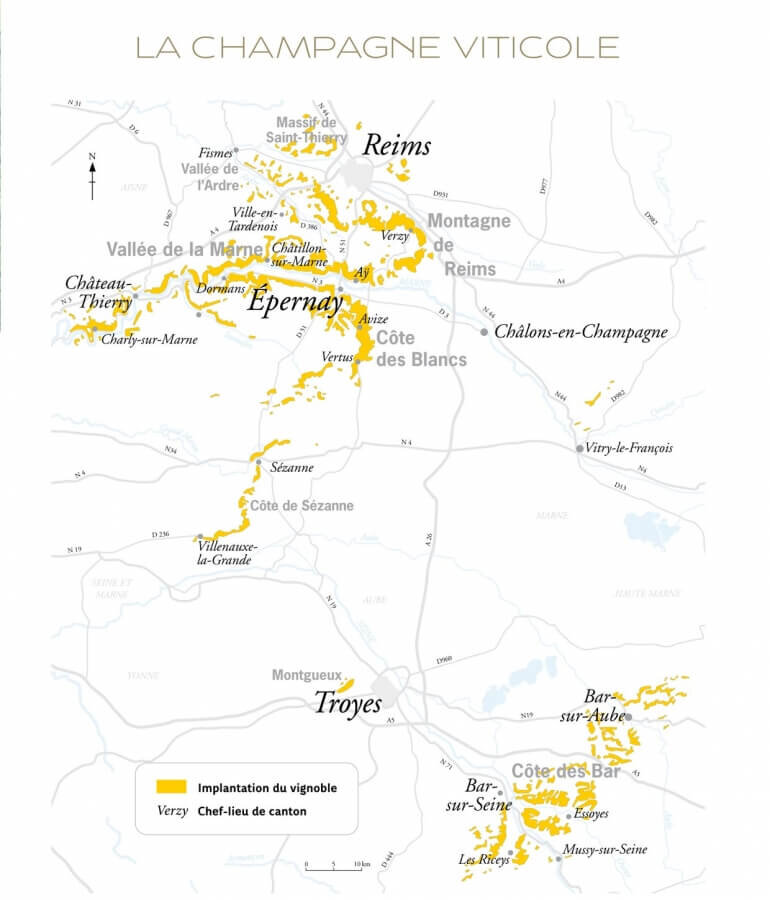

In 1927, the delimitation was defined. This indicates the geographical area from where the grapes can be used to make champagne (picture 1. Source: Comité Champagne). Before, there had been examples of cheap grapes from elsewhere in France used in the production. At the same time, the seven grape varieties for the champagne production were stated.

AOC (AOP outside France) followed closely after in 1936. It denotes a set of standards to secure champagne grapes a certain level of quality. The requirements includes the number of grapes per plant, their level of sugar, the pressure for the pressing and the length of time regarding the period of aging amongst others.

Nowadays these standards are managed by the INAO with a multitude of other AOC’s, that have joined since from all regions of France.

The work of the trellis

The trellis in the vineyards of Champagne (picture 2 above) is closely linked with the traditionally rather cool climate.

When the number of sunshiny hours is low, it gets more important to maximize them. That is the idea of the trellis. When we prune, we manage where the grapes will be placed as much as we may from nature’s choice. Then we use the wires of the trellis to lift the branches, and keep them in place with staples made of starch (picture 4). This will place the clusters where they get more sun, thus mature better.

The trellis also makes it possible for us to place the branches evenly along the wires to avoid having them sit together in a lump. This task takes us many weeks in the summer (picture 3) but will provide the wind a better chance of ventilating the foliage after rain. This practice minimizes the risk of diseases like downy mildew and powdery mildew. They have threatened the yields ever since they arrived in Champagne in the mid-1800s.

We also use the wires to manage the height of the vines as well as their length: maximum 1,5 meters between the rows and between 0,9 and 1,5 meters along the trellis as well as a defined area in the plot that is calculated according to the choice of width and length.

This will bring the total density of plants to approximately 8.000 vines per hectare, which is high compared to other regions. The idea is that the high density will force the vines to grow less clusters, because of the competition, created by the density. An idea that may fit a cool climate better than a warmer one.

The vines at work for decades

A vine can reach an age of several 100 years. Typically, the older the age, the smaller the yields despite the pruning, which is supposed to manage the vigor of the plant and obtain a certain number of grapes.

In the plots of Champagne however, the average vine is 30 years old, and the number is on the rise.

“We plant vines on the behalf of future generations and so we are eager to try to imagine the 2030s and even beyond.”

Typically, small companies keep the vines longer. In our company for instance, we do not replant before it is necessary, and we are not the only ones. It is expensive to renew a plot, and it takes many work hours. Anyway why change something if it works?

Our plots have been planted between the 1960s and 1980s. Still every year we plant some hundred vines to replace those who have died because of different wood diseases.

We currently maintain vineyards that we have taken over from parents and grandparents. Like them, we also plant vines on the behalf of future generations. Therefore, we are most eager to try to imagine the future circumstances in the 2030s and even beyond.

Let us get the temperature of what we do know, and then what we may suspect.

Temperatures in Champagne

The average temperature in Champagne has risen 1,1 degree Celsius compared with the period between 1960 and 1990. This means more sun, a bit less rain and slightly warmer nights.

Some of the consequences are earlier grape harvest and more sugar in the grapes.

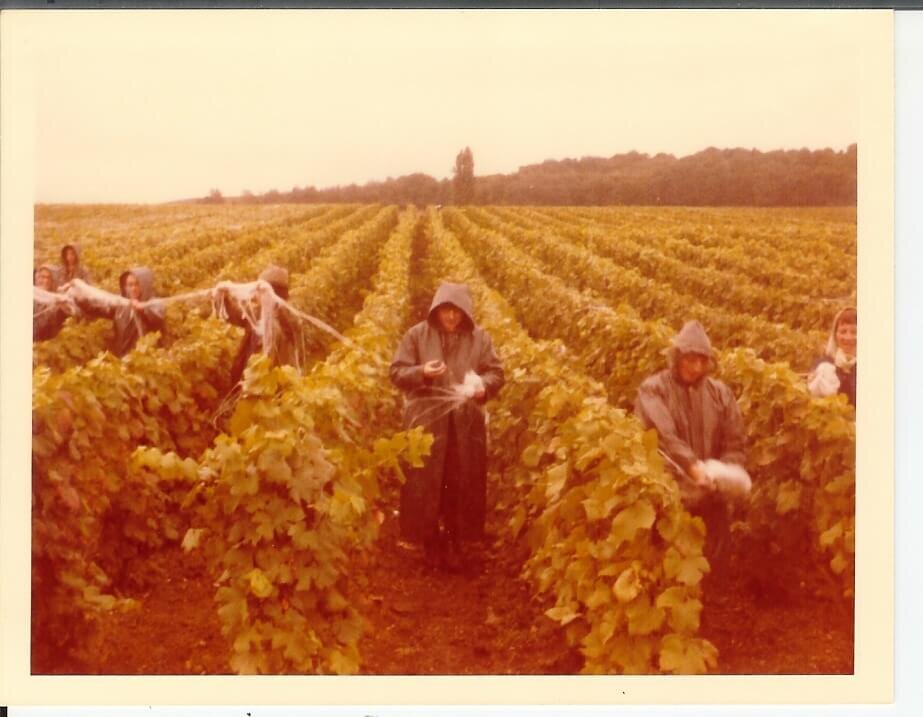

When I came to Champagne in 2003, I was wondering, if the enormous flocks of starlings in the autumn would not cause problems for the grapes. I was explained how big nets used to be put in place to cover the vines to prevent birds from feasting with the grapes before the harvest.

I saw an old photo from the 1970s, where the family dressed in green raincoats removes the nets just before the grape harvest in the plot of les Crochettes in Soulieres (picture 1 below). I even saw the nets, that have collected dust for decades in an old barn. They have not been used for a long time, because the grape harvest finishes before the starlings arrive.

Now and then the warming solves a problem.

More sun, more sugar

In 30 years, the grape harvest has moved 18 days forward. The climate of Champagne is not as marginal as it used to be when it comes to winegrowing. Today Épernay enjoys an average of approximately 11 degrees Celsius. It used to be 10 degrees Celsius which is not far from the traditional limit of winegrowing areas at an average annual temperature at 9 degrees Celsius.

More hours of sun fit the grapes of Champagne. The warmer weather in winter makes the buds develop earlier in spring. The cycle of growth from flower until harvest is shortened, some years down from 100 to 85 days. This means that the maturation takes places at a time where days are warmer and longer than in autumn. It allows the grapes to stock up more sugar. There is also more atmospheric CO2, says Comité Champagne, and this makes the photosynthesis work better (*).

More sugar in the grapes allows the must during the first alcoholic fermentation to develop up to 0,8% vol. more alcohol than before. Chaptalization – that is the process of adding cane sugar to the fresh must to reach a higher level of alcohol – may be of less necessity nowadays to obtain 11,5 % vol. alcohol, which is the target of the first alcoholic fermentation. Alain Gérard measures the level of sugar several times before the harvest begins (picture 2).

Note (*) The photosynthesis: Plants nourish themselves through the photosynthesis. The leaves absorb light, CO2 and water and change these to oxygen and sugar (glucose).

Malic acid and pH

Parallelly, the level of the sharply tasting malic acid has fallen, because the maturation of the grapes is more advanced than it used to be.

The acidity provides the distinctive freshness of a champagne, and therefore it is of great importance to maintain a good level of it for champagne to keep this major feature.

However, many Champagne wines go through the process of the malolactic fermentation. The purpose is to change the sharp malic acid into the more rounded lactic acid. This process begins spontaneously when the wine reaches a certain temperature. But it is possible to block it as well when you want to keep the malic acid and the sharper taste.

Another expression of the acidity in the wine is the pH. This value has only changed little these last 20 years despite differences between the years. According to the Comité Champagne it is linked with the level of potassium. If this remains low, the pH will stay low as well.

The level of potassium is decided in the vineyards. We can use less fertilizers, establish natural grasses or sow plants in the vineyards, plant vines, that are grafted on less productive stock (*) and press the grapes more softly and progressively to work with the level of this element.

Note (*) The most common stock to graft the vines of Champagne goes by the code of 41B, that fits chalky soils, and SO4, that fits soils with less chalk better. Finally, 3309C prefers soils with very, little calcium. Our vines are mainly grafted on the 41B, but we have some SO4 as well.

The composition of the grapes

A third parameter, that depends on the climate, is the composition of different minerals in the grapes. This will show during the vinification.

For example, when the grapes are low on nitrogen, the fermentation is at bigger risk of being disturbed. We had this experience as we pressed Chardonnay-grapes for our first single champagne, Solliage in 2013, and the grapes were low on nitrogen. Since then, we pay more attention to this phenomenon.

Basically, what this means is that we have already changed methods both inside and outside to meet new challenges in the vineyards, that are linked with a warmer climate.

Now, let us have a look at the more recent years in Champagne.

Records of heat since 2015

In the region, we qualify 2015 as the first in a series of years, that are warmer than before.

These years are not alike, but they have some features in common. For example, big amounts of rain in the winter and little or no rain at all in the summer, earlier grape harvests, and a different pattern of maturation, that we follow more carefully than before.

“These years are not alike, but they share a new pattern regarding rain, harvest dates and maturation.”

In 2018, the thermometer jumped over 42 degrees Celsius one day in July in Champagne. Here, this is still the record for a heatwave.

Soulieres did not pass this level. However, it was still warm enough for quite a number of Pinot Meunier-vines in several of our plots to be burnt into a completely dry state way on the other side of dry raisins. These clusters sat on the sunny side with absolutely no protection (picture 3 above).

Since 2015, Meteo France qualify each year as the warmest.

The work with the foliage

Such extremes may require a better protection of the grapes.

For years, we used to remove some leaves to allow the grapes access to more sunshine. Henceforward we may keep them instead to protect the grapes against heat damage.

In the summer, the activity of the rognage is done to balance the vigour of the plant. We send a wine tractor through the lines to cut leaves and branches on the top and on the sides. Usually, we begin around the flowering most years in June and continue once per week until the growth is finished in August.

This is an example that show how we may adapt our methods to work in a changing climate within the current AOC-standards.

Interestingly, the researchers of Comité Champagnes investigate how the maintenance of the foliage may influence the content of malic acid in the grapes.

Shallow ploughing

Another possibility to help the grapes preserve their acidity is to work with shallow ploughing between the plants. In our company, Alain Gerard has some years of experience with this work. He develops the methods regularly with a growing number of tools behind the tractor (picture 1 below).

For the time being, the philosophy is to disturb the life in the soils as little as we can. We do not mess about everything at each passage. The idea is to keep the vines clean and let the rest look after itself. However, we cannot set it all free (read more here).

Competition for nutrition

The vines are visibly under pressure in the hard competition for water and minerals with the other small plants and grasses in the lines. Subsequently, we have less yields than before, though normally still enough to reach the quota.

The competition shows on the vigour of the vines as well, and we have not found a solution easily at hand.

Several times, we have tried to sow various cereals in the lines to contribute to the nutrition of the soil rather than extract it only (picture 2). We have no final conclusion yet but remain rather confident.

The results of the shallow ploughing are that the soil remains moist in the upper parts. Despite no or little rain, the work helps the soil not to dry out completely like the surface.

Learning by doing

However, it is obvious, that the ploughing is a process in constant development.

Each year comes with specific sometimes unique challenges. Sometimes no one never saw anything like it.

The answer is not business as usual but develops with a combination of knowledge and imagination. Sometimes courage is needed as well.

The taste of the grapes does not stay the same either. This is certainly a challenge when you aim at making champagne of the same taste each year and have few wines to blend. We decided that o ur single vineyard champagnes taste their year. We like the idea. It is also necessary the way we work.

Experimental plots with more spacing

Another approach of the competition between small plants and vines in the vineyards will maybe come from experimental vineyards.

Comité Champagne and INAO have experimented with vines planted in wider lines and with more spacing between the plants since 2005. The results have been published in March 2021.

The experimental plots have a lower density of between 3.790 and 6.170 vines per hectare. Otherwise, the density is approximately 8.000 plants per hectare. The vines are pruned to reach a maximum height of 2,20 meters, which is one meter taller than today.

The conclusion is that the vines in the experimental plots are a bit less susceptible to freeze in the spring, and that the grapes keep the acidity a bit more along with a slightly lower pH. The yields are smaller but of a sufficient size to reach an average quota according to Comité Champagne. But the competition for water between plants remains similar.

New method allowed from 2023

The project with its advantages as well as drawbacks has been discussed all summer 2021.

One major problem for the opponents is that champagnes, made of grapes from experimental plots, are different. Another problem, according to the opponents, is that the new measures may introduce a more industrial and large-scale conditions of production.

Amongst the opponents are many smaller and independent growerbrands. Our own opinion is that this method seems temporary as it does not provide real answers to challenges regarding global warming.

Still, a majority of the board of the Association of winegrowers in Champagne, voted yes this summer 2021. Therefore this new way of organizing a Champagne vineyard will be authorized from 2023.

However, it remains a choice and not a must.

Esthetical quality of the landscape

The landscape of the Champagne vineyards was classified within the Unesco-charter of cultural landscapes in 2015. This is a source of much pride in the wine profession of the region. The looks are part of the classification making it important to meet certain standards continuously (picture 3 + 4: Cultural landscapes of Champagne: view towards Épernay from the vineyards of Chavot-Courcourt and from Hautvillers).

With the new method, the vines can be pruned up to one meter taller than the traditional ones. This is quite a visual difference, yet the esthetical quality has been evaluated to be neutral or even positive.

But what about the current grape varieties and warmer temperatures?

Warming and wine regions

In 2020, a group of researchers from all over the world, amongst them participants from INRAE and Bordeaux Science Agro in France, presented their shared research on the warming of vineyards globally with projections of the possible consequences of further warming (*).

56% of the wine areas of today may disappear at an average warming of further 2 degrees Celsius by 2050 and 85% at an average warming of 4 degrees Celsius by 2100.

One way to meet this challenge is to plant grape varieties that are adjusted to the altered conditions. This would reduce the loss with 50% in 2050 and one third in 2100 according to the results of the group.

Where does it take varieties like Pinot Noir or Chardonnay in Champagne?

Note (*) I. Morales-Castilla, I. Garcia de Cortazar-Atauri, B. I. Cook, T. Lacombe, A. Parker, C. van Leeuwen, K. A. Nicholas, et E. M. Wolkovich, Diversity buffers winegrowing regions from climate change losses, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences January 27th 2020.

New and ancient grape varieties

The group of researchers point at the great importance of knowing how the grape varieties of today may adapt to different and warmer conditions.

“We can expect the flexible Chardonnay under warmer conditions but what about the cool cousins of Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier?”

In Champagne, we can expect that the flexible Chardonnay will accept the challenge of different and certainly warmer conditions. But what about the cool cousins of Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier?

A possibility may be to search for ancient varieties, maybe mutations, that were given up, because their cycle of growth did not fit into the climate of the past. Maybe a variety with grapes which mature late would fit well into a warmer climate as they would mature after the warm summer.

This kind of questions may find their answers when the development of vines in experimental vineyards is followed for years and decades as well as the wine, that can be made with their grapes. Just like the experiment with the larger lines in the vineyards.

Research combining the phenological stages of the vines with scenarios for future warming show that the northern limits of viticulture may reach as high as 55°N w(southern part of Denmark). Similarly, future winegrowing in Southern Europe may be less endangered than previously thought through new methods fitted to a warmer climate in combination with the grat adaptability of the vine itself (Cukierman, Quénol, Bouffard).

Choice of stock (*) may play a central role. Traditionally, it has been chosen considering yields and vigour. Today, researchers work on developing stock that adjust better to periods of drought.

(*) A vine has two parts: the upper part, the scion, is the fertile part where the grapes develop, i.a. the Chardonnay, the Pinot Noir or another vitis vinifera-type. The root part, the stock, is an american type of vines (for instance vitis represtris), that is not endangered by the Phylloxera-insect that destroys the roots of vitis vinifera-types. This is why a vine is grafted from these two parts.

Wine lovers and winegrowers in key roles

New grape varieties may be part of how we can meet warmer conditions. Therefore, an important field of work will be to inform and invite champagne lovers about new experiences in taste.

Winegrowers will also have to prepare for more changes than new work methods. And some are:

In a survey in Le Vigneron Champenois, Comité Champagnes magazine for the champagne profession, 89% of 289 respondents from different sizes of champagne companies were positive regarding experiments. 24% were ready to try new grape varieties.

Obviously, the ongoing typicity of the Champagne-wines is central for many respondents. It is particularly important to search for solutions that will enable the wines from Champagne to keep a good level of acidity.

For the time being, we regard the exchange of experiences and solutions with neighbours and colleagues as an important stepping stone on this shared trail into the future.

“We regard the exchange of experiences and solutions as an important stepping stone on this shared trail into the future.”

Local and global decisions

We set out with a question of what to expect in 10, 20, 30 years. Few are better placed than the researchers with their forecasts. Therefore, they will get the last word:

The future of classic wine regions will depend on human decisions, they write. Further: the methods of work and choice of grape varieties can be carried out locally, but the future of wine regions will depend on political and societal decisions at a global level.

“At local level, the adaption of work methods in the vineyards may save some wine areas, at least partly, from disappearing.

They continue:

“But on a global level, the future of the world’s wine regions will depend on political and societal decisions that will be made in the next years, and the emissions of greenhouse gasses that will develop further global warming,” says INRAE and others in a press release from 2020.

None of us can know exactly how to move forward. However, we may expect that business will not be usual and teach ourselves to deal with change as it unfolds.

Some sources:

Agrisource : Planter des cépages adaptés (in French)

Bonal, Francois : Histoire du champagne (site : Maisons de champagne ) (in French)

Comité Champagne : S’adapter au changement climatique (PDF) (in French)

Cukierman Jérémy, Quénol Hervé, Michelle Bouffard: Quel vin pour demain, Dunod 2021 (in French)

INRAE : Adapting winegrowing regions to change (in English)

Plan dépérissement vigne : État des lieux en Champagne (in French)

Le Vigneron Champenois, Mars 2021 ( (in French)