Change of climate gave us champagne

Many of us notice change related to warmer weather. But did you know that climate change has changed the wine in Champagne before. Actually the bubbles were a phenomenon that began to occur in a period that was more cold.

Today, the change of temperatures is headed for the opposite direction. What with the bubbles then? The next paragraphs outline the history of the Champagne climate then take a glance into the near future.

It probably all began with the Romans.

The Romans and the wine

Nobody knows excactly when the first vines took root in the Sézane-region of Champagne.

The Romans brought vines when they arrived in todays’s Marseille. Gradually the rest of the then Gaul became a Roman provins during the 1st century before B.C .

As they fought their way north, these Romans moved the limit of growing vines with them. At least up to Burgundy.

The first definite traces from vinyards appear in Champagne around the 4th century A.D. The grapes were turned into wine without bubbles for the next more than 1.000 years.

The great period of the still wine

The wine from Champagne had excellent opportunities to reach beyond the area.

The French kings were crowned in the cathedral of Reims from the late 400s (picture 4). During the coronation festivities, the wine at hand was served as well. In this way, the wine from the region became known elsewhere.

As the roads in those were bad, dangerous if there were roads, it was quite an advantage to transport the wine barrels to Paris by the river Marne, a confluent of the Seine. In this way, the winemakers could rather easily send their wines to the French king or further on somewhere in Europe.

Then from the 1300s the weather gradually got colder in the Northern hemisphere.

The little Ice Age

The period from the early 14th Century until mid 19th Century is known as The Little Ice Age today. On average the temperature dropped 0,6 degrees Celsius in the nNorthern Hemisphere with devastating consequences.

Where did it come from? The explanation is likely complex. Amongst possible causes are a volcano eruption, lower sunspot activity with less CO2 in the atmosphere (see Some Sources). As the climate were unusually mild between 1000 and 1300 (*), the difference would seem even more dramatic.

Forced by the cold, the last Norsemen left Greenland in the 1400-hundreds. Some twohundred years later, the thermometer hit the lowest point. Denmark and Sweden were at war (again), and as the Danish strait of Storebælt (**) froze completely in 1659 the Swedish army could walk to the island of Zeeland and besiege the Danish capital of Copenhagen. Afterwards the regions of Skåne, Halland and Blekinge became Swedish. Further south, it was the end of growing oranges in Provence, and the colder temperatures would change the conditions of winemaking in Champagne as well.

Note (*) The Medieval Warming Period

Note (**) Nowadays the bridges between the islands of Funen and Zeeland span a distrance of 17 kilometers.

The temperature change in Champagne

With the drop of temperatures, the vineyards of Champagne were situated at the northern limit of where grapes could mature. Shorter summers and harder winters meant that the grapes were picked, pressed and fermented later in the year. This cold simply stopped the fermentation before it was finished. Then as temperatures warmed up again the following spring, the yeast would resume and finish.

These two fermentations in part were similar to what would be the two fermentations of the Champagne-method. Furthermore, the climatological conditions would mean that the harvested grapes were not very mature. The resultat was a wine, rather low on alcohol, which is perfect when you want to ferment the wine double. This second time however is how that wine will become sparkling. These bubbles were a kind of naturally occuring malfunction.

Please don’t imagine a pressure of 6 bar like inside the bottle of champagne, you may have at hand. At this time even before the birth of champagne, the wines were kept in barrels. Subsequently the carbondioxide disappeared naturally after some time. But, bottomline the wines were not still the same way as before.

This is how things were in Champagne, when a monk arrived in the monastary of the village of Hautvillers above Épernay in 1668. One of his many duties would be to deal with the production of wine , which was a source of revenue of the place.

Dom Perignon made great wines

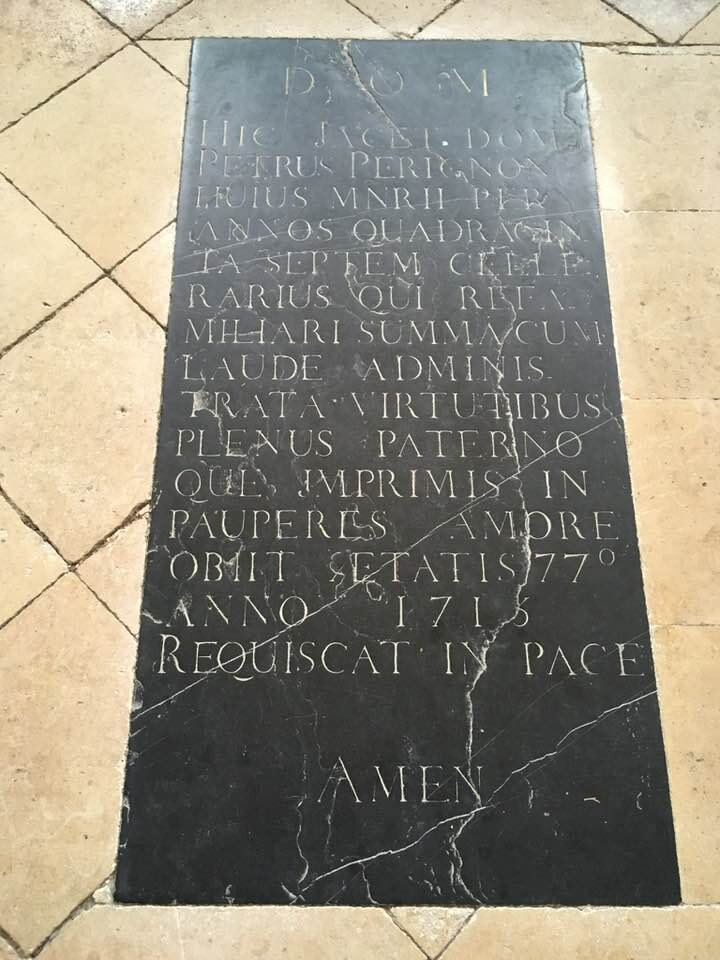

The name of this monk was Pierre Perignon. You may have heard of Dom Perignon as the inventor of champagne even he most probably never made sparkling wine deliberately. More likely he would have tried to get rid of the carbondioxide. the sparkling effect in the wine barrels would not be appreciated for decades to come.

Grapes arrived to the monastary as tithe, a kind of taxes that peasants had to pay to the church. These yields came from many different vineyards, on top of those owned by the order itself. Dom Perignon would give directions on how to proceed with these many different grapes.

He managed this task with such a talent, that his wines from the late 1600s would become the most expensive from Champagne. The income made it possible to rebuild the buildings of the monastary that had been destroyed several times due to wars.

He is buried in the church of Hautvillers where his epitaph is visible in the floor in front of the altar (picture 3 above).

(*) Dom is a title, used in some orders like the Benedictines in Hautvillers.

The method of Dom P

In our days none of the notebooks of Dom Perignon still exist. His methods however, have probably survived via his student, brother Pierres, written works, that still exists.

This material credits Pierre Perignon for the idea of to press different cru (communes) separately and very carefully to avoid colouring the must. Must from white and black grapes could be mixed into a vin gris (grey wine). This is still practise in Champagne.

“These blends turned out to be a very good idea in the cold climate where grapes matured rather heterogeneously. ”

Furthermore, Dom Perignon had a habit of leaving clusters outside the window overnight and taste them the next morning. He would then make use of these tasting impressions in combination with information about climate and the development in different plots to decide how to assemble different wines.

These blends turned out to be a very good idea in the cold climate where grapes matured rather heterogeneously. But when wines made of these uneven grapes were blended with talent, they would complement each other in a joint expression, better than what they would achieve on their own.

This composed wine wine is still the basis of a classic champagne in current times.

In the mid-19th century, the winemakers in Champagne began to blend wines from different years. When the champagnehouse Pommery (picture 1 above) released a low-dosed (*), “brutal” bottle of champagne on the important English market in the late 1800’s, the emblematic brut sans année had taken shape.

It dones get more classic, and this type of champagne is by far still the biggest seller.

Note (*) The dosage will decide for the sweetness of a bottle. It is added at the time of disgorgement. Before Louise Pommery invented brut champagne, the wine was a very sweet with several 100 grams of sugar in a bottle. The spectrum of the brut is between 0 and 15 grams per liter. The sweetest dosage is called doux and begins at 50 grams per liter.

From London to Paris

As Dom Perignon worked in his cellar in Hautvilers, the recent sparkling effect of the Champagne-wines was increasingly met with interest abroad. But not in France. The old Sun King did not appreciate the unquiet wine.

In England, the elite imported barrels with wine from Champagne. When the wine was served, it became fashion to mix with sugar to increase the sparkling capacity. In the early 1700s, barrels were shipped from Champagne with instructions on how the recipients could bottle the wine themselves and close tightly to let the fermentation finish directly in a bottle. This saved some more of the bubbles.

This fashion travelled back to the French side of the Channel and spread in Paris after the death of Louis XIV in 1715. Dom Perignon died the same year.

The bubbles got their momentum i den såkaldte Régence-periode, hvor Philippe d’Orléans styrede landet på barnekongen, Louis XV’s, vegne. Philippe is remembered for his dinners in Palais-Royal in Paris with lots of gambling, mistresses and sparkling wines from Champagne.

From those early days, champagne made it all the way through the galant 1700s (picture 2 above, source: Comité Champagne: “Lunch with oysters”, painted by Jean-François de Troy in 1735).

Early champagne bottles

The customers were the elite of the time: royalty, nobility and the top of the bourgeoisie. They made the bubbles highest fashion for those who could afford it.

In 1735 the producers in Champagne were allowed to bottle their wines in a bottle. This allowed to preserve the bubbles much better.

It was extremely expensive to produce the new wine. Now a big job to refine the new wine began.

The technological development

The waste of bottles was just enormous: up to 50% in the worst years. Bottles would explode in the caves, because the pressure some years would be too strong. The connection between years, sugar and the development of the pressure inside the bottle had not yet been discovered. Another major problem was, that the bottles were not not industrial and like the uniform, strong quality of today.

The obstacles meant that big investments were necessary to produce champagne. Only people with venture capital could join this new adventure. The first champagne houses were founded by people who had already made money in other industries.

For instance a certain Francois Clicquot in Reims. His family had made a fortune trading textile, and the money - or some of it - was invested in the production of the new type of wine. However, it was his widow who would eventually make the house known all over Europe.

Many of these companies had not already been involved in the traditional and wellknown still wine from Champagne. The following 2-300 years these start-ups of those days would push the technnological development, that would eventually lead to the transparent, sparkling wine in a reinforced bottle, that we know today.

Work in the countryside, party in the city

Outdoors, in the vineyards, it was still peasants who did the work. Tasks, that have changed surprisingly little since those days.

Before The French Revolution, the land was owned by the nobility and the Church mainly. After the Revolution, les négociants, who made the wine, and the peasants who cultivated the land, were given the opportunity to buy land. The peasants would own little land, which made it impossible for them to make their own wine. But they still stuck to the land. Many continue to own little land, but winegrowers and farmers still own up to 90% of the land.

However, the different tasks had become very difficult some years in the wake of colder temperatures according to sources from the 18th and 19th centuries: Frost, cold weather, rain and some years no grape harvest at all.

It is hard to imagine a greater contrast than between the hard life in a winegrower’s family and the elegant and everlasting feasts in the gilded cercles of the customers.

Well into the 1800s, the original, still wine without bubbles was still the main produce from the region. And they still had a reputation of being amongst the best wines from France, at least those from certain communes.

Around the 1850s the word champagne began to appear in print on the labels. At the same time, the champagne had become an absolute necessity at any party.

The big party

The price of a bottle had gone down, enough for the sparkling joy to spread more in the upper classes of society.

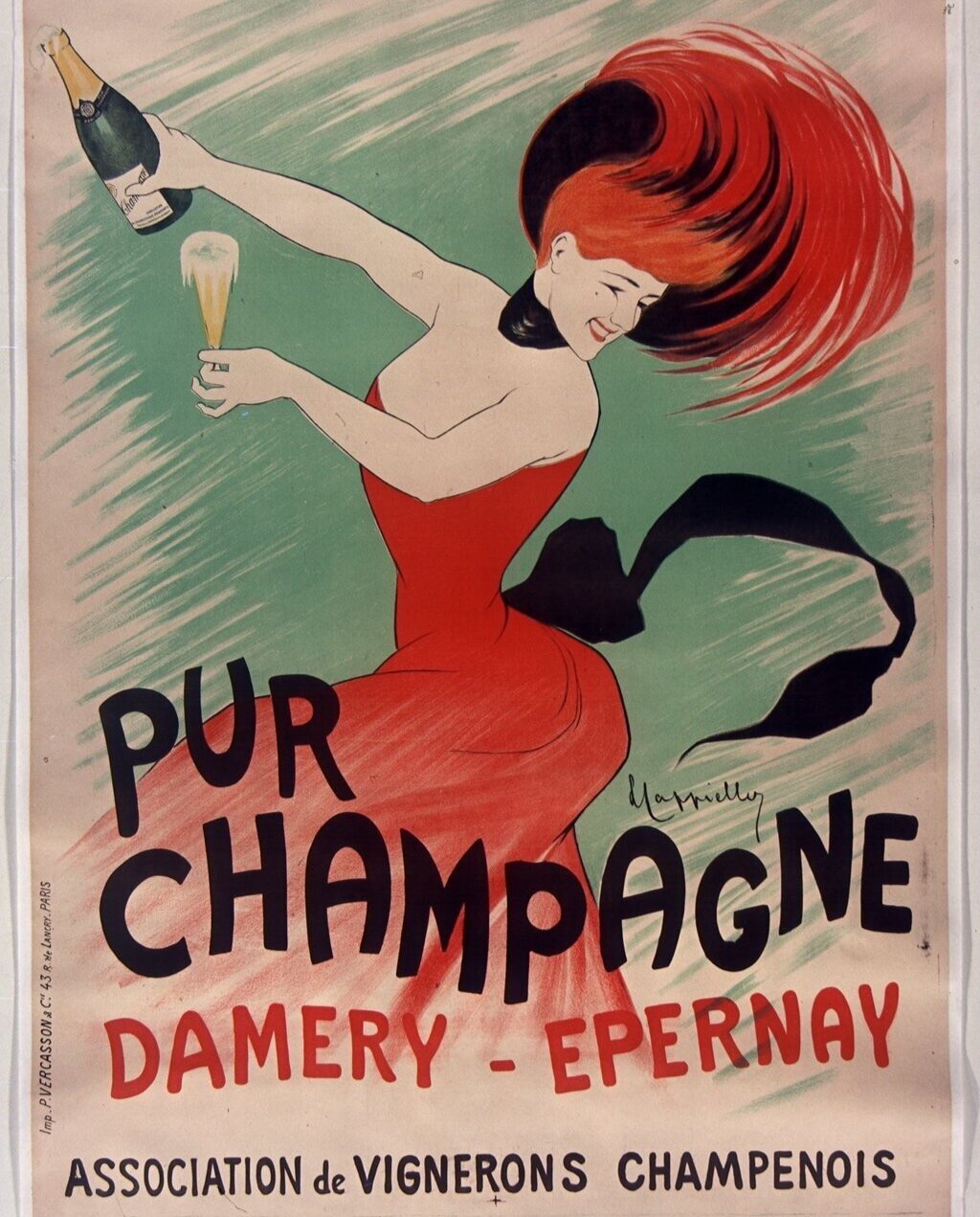

Champagne had become an obvious participant in parties in the full spectrum from the imperial celebrations to the bohemian nightlife of the capital. When the Second Empire and Napoléon III came to an end in 1870, the new politicians in power continued the course during the Third Republic. The artist Leonetto Cappiellos poster, made for winegrowers in the village of Damery (Picture 1 above: Source: gallica.bnf.fr / BnF) is just one example amongst many from this Belle Époque.

As the 1800s became the 1900s, the production of champagne were multiplied by ten from 300.000 bottles in the years around The French Revolution in 1789 to 28,5 million bottles in 1899 (picture 2: source: Champagne Pommery: worker in the caves).

This was no small achivement, it would place the wine without bubbles in the shade. There was not enough grapes to maintain a big production of both types of wine, and the demand for bubbles had now taken the lead.

But the wine continues to live on in Champagne. It has an appellation of its own: the Coteaux Champenois in a red and white version and furthermore the rosé, le Rosé des Riceys, the third appellation in Champagne.

The 20th century

During the 20th century, the market and the produktion of champagne has gone up and down like a rollercoaster, often in line with crises and wars. Champagne is a product that follows the follows the economic situation in society very much. The bottom line this far has always been growth and more value in the aftermath of each crisis.

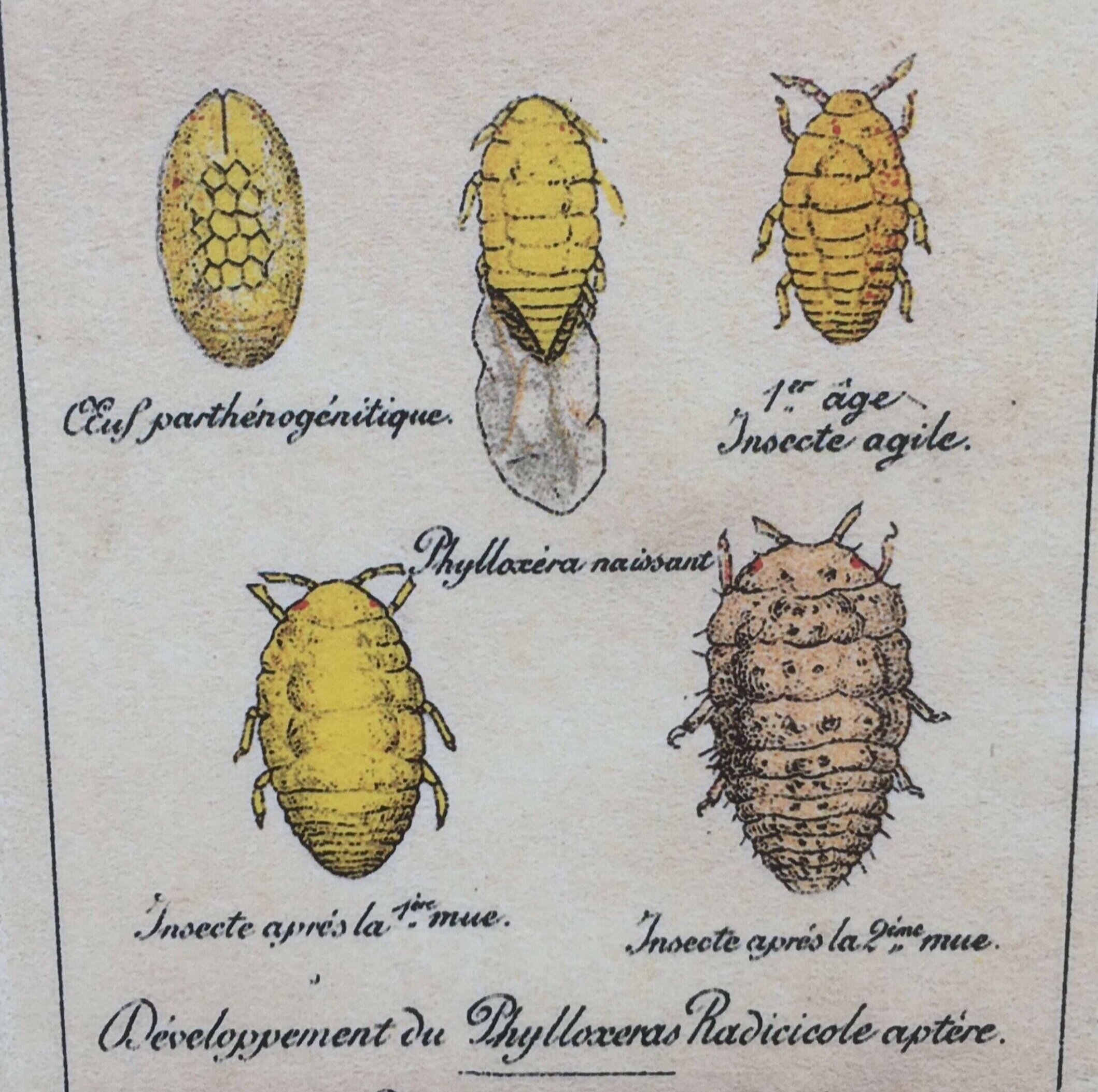

The 20th Century began with a biological crisis in Champagne and in other European vineyards. The Phylloxera insect destroyed the vines completely (picture 3 above). Another disaster followed, this time political. What would become known as The Great War took place in some of the vineyards of Champagne, amongst many other theatres of this war. The Interwar years - for the lucky few the Roaring 1920s - came to an end with the stock market crash on October 29th 1929. The crash was followed by the Great Depression, a long and severe worldwide economic depression. Several decades would go by before it would become worth it to grow grapes in Champagne again for many landowners who could do differents kinds of farming instead of growing grapes. From the 1950s and onwards, it gradually became more interesting to grow grapes again.

As the 20th Century came to an end, the sales of champagne had multiplied by ten once more to approximately 300 million bottles sold.

Organizing the profession

Meanwhile the profession had developed. The techonological development had made it possible for more persons to buy equipment to make their own champagne.

The numbers are significant: There were 1.300 winegrowers who made their champagne - the récoltants-manipulants - before World War II. 30 years later, this number had almost tripled to 3.000.

During World War II, winegrowers and champagnehouses established an agency with the purpose to negotiate with the occupying power together. The Germans demanded champagne handed over for the officers. This was the beginning of the Comité Champagne.

Today the organisation has a multitude of functions. One is research in all sorts of knowledge in grape varieties, their growth, winemaking, climate amongst others. Data of climate and their analysis are found there though it is not always scientists of the Comité itself who performs the research.

The data on the development of the vines is collected locally in each village by the correspondents of the AVC (*). In Soulières, Alain Gérard gathers and reports dates and development regarding frost, first leaf, flowers et cetera.

This is interesting since the development of the vines is closely connected with climate.

Note ( *) AVC is an organisation, that was created by the champagnehouses originally with the purpose to spread knowledge about how to replant the vineyards of Champagne after the Phylloxera-crisis, that destroyed close to everything. In our days, the AVC deals with technical aspects of winegrowing and the collection of data regarding the weather and the growth of the vines from all villages of the region.

Warmer climate in the area

In the Champagne-region, the average temperature has increased 1,1 degree Celsius compared to the period of 1960-1990. The vines are not grown in a marginal climate any longer like in the last 500 years since the Little Ice Age.

This warming made a small beginning in 1850, and it became intensified by human activities from the second half of the 20th century.

This far, the warmer temperatures in Champagne make the grapes mature better. But also that the period between the flowers and the mature grape is reduced. 96 days on average used to separate flower from grape. In more recent years, this span has been as reduced as just 82 days (please check the graphics above, that links to a report with further information in French).

At the same time, the distinctive acidity of champagne is not a birthright any more. Today, we have adapted our work methods in the vineyards to take better care of it. Likewise, we measure our grapes rather carefully before harvesting them to pick at the best moment.

In 30 years, this grape harvest has moved 18 days up in the calendar to begin on average in early September and some years even in August.

New ways of working

In the vineyards, the new ways of doing things can be spotted all over the region.

Herbicides are on their way out. Grass and other green plants between the lines of vines move replace the naked land of yesterday. The new methods mean competition for access to the minerals of the soils ( for instance for nitrogen) and for water as well. This competition influences the vigour of the vines, and also the amount of grapes, their taste and subsequently the taste of the champagnes as well.

The big unknown, of course, is the question of what will happen with champagne when the climate becomes even warmer than now?

This is an interesting question, and it can only be answered partly.

The optimistic projection

Especially since 2015, warmer summers with very little or no rain have become more common in Champagne.

The pictures above are from four different summers this last decade: in 2013 the vines were in flowers in early July with late harvest in early October which was not seen since the 1980s (picture 1). The next picture shows grape samples from early September in 2014, which was a more classic year in Champagne with a warm periode in the spring and in the weeks before the grape harvest in combination with a very wet and cold summer (picture 2). Then 2015 gave us a warm summer and a quite early grape harvest with rather cool temperatures (picture 3). Finally, 2021 brought an incredibly and disturbing amount of rain combined with rather warm temperatures was (picture 4).

But even the years vary in the vineyards, the average temperatures go up only.

If the global warming will stay below two degrees Celsius (optimistic scenario), the effect of it will contribute to better the grapes for champagne, says the experts of the Comité Champagne. More sun allows the grapes to stock up more sugars.

The traditional champagne blend of different grape varieties, plots and years may be a choice then more than a necessity in the production of champagne. When the grapes obtain the wanted quality singlehandedly, it will allow small producers like ourselves to make vintage champagnes based on the grapes of the year. Our own singles-series of single plot and/or monocépage-champagnes (one grape variety) are examples.

But the warming may not stop at two degrees Celsius.

The possible climate of the future

A study in climate change and the vineyards of Champagne worked on possible implications within different future scenarios based on the IPCC standards (*) back in 2010.

Not surprisingly, the results showed that a significant warming will imply major change. Especially the pessimistic scenario may provoke such damage to the vines that this will create major damage for the activity in the vineyards in the 2060s (Beltrando & Briche 2010).

In today’s reality and on our individual scale, we implement new methods based on what we think is better and/or necessary.

You can read more about our recent measures in the Greenprint part of the site with older examples still available on the blog. New material will be published now and then as we find the time to write it.

(*) IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change) SRES scenarios: B1 (optimistic), A1B (intermediary), A2 (pessimist).

Research and experimenting

The ongoing warming no matter future size will make it necessary to change growing methods in Champagne and elsewhere. A major change however, is not initiated bottom-up from an individual level.

Within an appellation like that of champagne, a wide range of requirements regarding outdoor and indoor production must be met by everyone involved. Comité Champagne in cooperation with champagne houses and growers will have to find the unknown quantities of the equation to decide for a set of requirements that will fit the future, based on research on one side and experience on the other.

The researchers in the Comité Champagne have installed 10 hectares of experimental vineyards. For decades, they have made experiments there with for instance density, grape varieties and trellis and pruning systems.

During the summer of 2021 the so-called “vignes semi-larges” were discussed fiercely. This method comprises more width between the lines and greater distance between the individual vines. A majority of representatives in the Association of Growers (the SGV) eventually voted this new method in as one possibility amongst others (Please read more here). However, as this does not meet all challenges of warming (competition for water for example), it seems temporary to us. And we have no time and no investment available for intermediary solutions.

Before we quit, let’s revisit the past of Champagne: the original wine of the Kings that was not sparkling.

You see, this year, 2021, several champagne brands introduced new wines, Coteaux Champenois, in their assortments.

It is tempting to interpretate this as a step that connects today with the warmer Middle Ages on the other side of the cold centuries that gave us the sparkling champagne, that will hopefully throw parties and be enjoyed for many more years to come.

Some sources:

Bonal, Francois : Champagne Guestbook (Maisons de Champagne) (in English)

BBC: Volcanic origin for Little Ice Age (in English)

Beltrando & Briche: Changement climatique et viticulture en Champagne : du constat actuel aux prévisions du modèle ARPEGE-Climat sur l’évolution des températures pour le XXIe siècle », EchoGéo [En ligne], 14 | 2010, mis en ligne le 16 décembre 2010. (in French)

Britannica: Little Ice Age (in English)

Comité Champagne (former CIVC) ( (in English)

Dossier presse changement climat (PDF in French)

GEUS: Arktisk havis startede Den lille Istid (in Danish)

Godinot, Chanoine Jean: Maniere de cultiver la vigne et de faire le vin en Champagne (in French)

IPCC: Scenarios (in English)

Météo France: Réchauffement climatique observé en France (in French)

Nationalmuséet: Den lille Istid og industrialiseringen (in Danish)

Nature: Last phase of the Little Ice Age (in English)

Zambri, Robock: Volcanic Eruptions as cause of Little Ice Age (in English)